Media is abuzz with upcoming 27th constitutional amendment. Though speculations have been in media since last few months, but a day before yesterday’s meeting of Prime Minister along with PML (N) with Asif Ali Zardari and later Bilawal Bhutto’s tweet on X, opened the flood gate of discussion on media and social media. As always, there are varied opinions on amendment but it is without any argument a legal and constitutional way to bring reforms in constitution. Pakistan’s federal government, led by Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s PML-N coalition, is fast-tracking the 27th Constitutional Amendment as the logical sequel to the 26th, passed just weeks earlier in October 2024, as media commentators observe. The 26th had already handed parliament—rather than the senior-most Supreme Court judge—the power to appoint the Chief Justice and to form a Judicial Commission dominated by elected representatives. Critics called it a death-blow to judicial independence; the government hailed it as democratic oversight. The 27th now aims to create a separate Federal Constitutional Court for constitutional disputes, restoring executive magistrates to clear district-level backlogs, and reversing key devolutions enacted by the 18th Amendment in 2010, media reports.

The 18th Amendment had been a landmark: it abolished the president’s power to dissolve parliament, devolved 17 ministries—including education and health—to provinces, and locked in provincial shares of the National Finance Commission Award. Provinces gained fiscal and policy autonomy, but the center now argues this fragmented education standards, stalled population planning, and left Islamabad with too little revenue to service $130 billion in external debt.

As per reports in media, The 27th amendment would recentralize education and population welfare under federal ministries, scrap constitutional guarantees for provincial NFC shares, and enshrine local-government elections in the Constitution. Amendment also aims to fix deadlocks in appointing the Chief Election Commissioner.

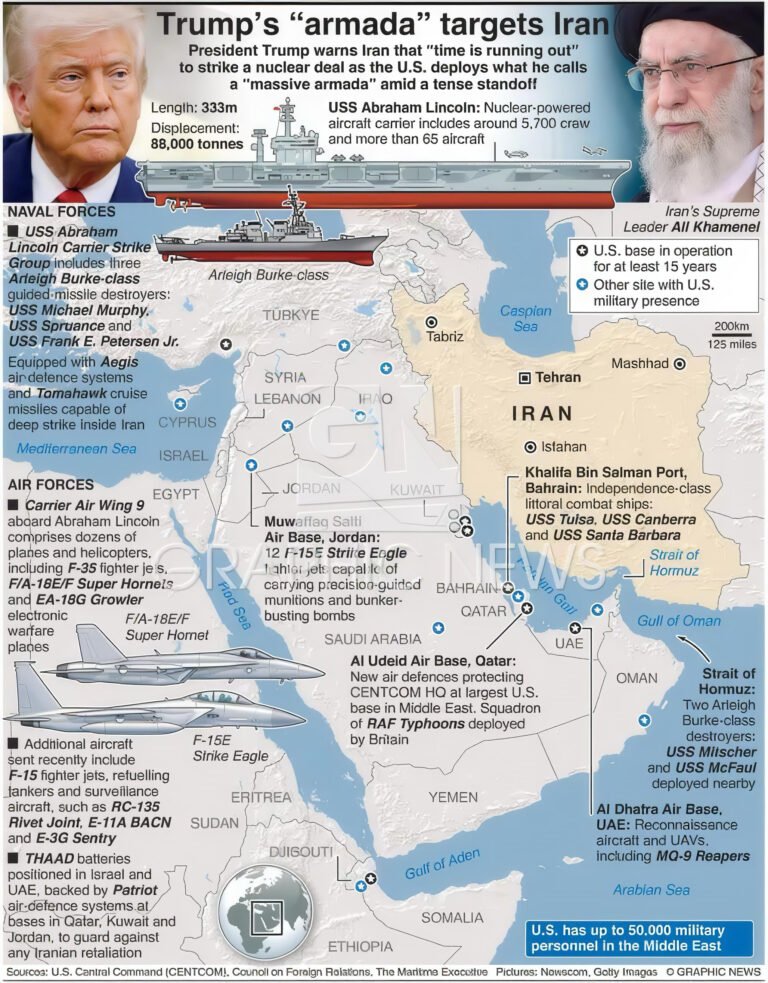

The government’s pitch is blunt: courts are choked with 2.5 million cases, provinces hoard funds, and the military needs legal clarity amid border tensions. The PPP’s vote on November 6, 2025, will decide if the coalition secures the two-thirds majority. If it passes, the amendment will recentralize power and reshape Pakistan’s federation; if it fails, the 18th Amendment’s provincial gains—and the 26th’s judicial overhaul—may yet survive intact.

Pakistan’s proposed 27th Amendment would push its 1973 Constitution toward a stronger federal center and weaker checks and balances, aligning it more closely with Britain’s flexible parliamentary sovereignty than with the U.S. model of rigid federalism and judicial independence.

In terms of federation strength, the 27th would recentralize key powers—education, population welfare, and fiscal flexibility—by reversing parts of the 18th Amendment’s devolution and removing constitutional locks on provincial shares of national revenue. This would allow the center to split provinces or create federal territories without provincial consent, making Pakistan’s federation far more centralized. By contrast, the United Statesmaintains a balanced federation: states control core functions like education, health, and policing, and the federal government is limited to enumerated powers. The U.S. Senate gives even small states equal voice, and states can sue the federal government in the Supreme Court. Britain, being unitary, has no entrenched provincial rights—Parliament can devolve powers to Scotland or Wales and revoke them by simple majority, much like Pakistan’s center would gain under the 27th.

On checks and balances, the 27th weakens judicial autonomy. Building on the 26th Amendment’s parliamentary dominance in appointing the Chief Justice and forming a Judicial Commission, the new amendment creates a separate Constitutional Court likely answerable to political forces, while restoring executive magistrates to bypass regular courts. This erodes separation of powers. The U.S., in contrast, features strong checks: life-tenured Supreme Court justices, Senate confirmation of judges, and the ability of states to challenge federal overreach. Britain has no formal checks against parliamentary sovereignty—there is no written constitution, and courts cannot strike down primary legislation. Executive and legislative powers are fused in the Cabinet.

Amendment processes also differ sharply. Pakistan requires a two-thirds parliamentary majority and presidential assent—achievable but frequent (27 amendments in 50 years). The U.S. demands two-thirds of Congress plus ratification by three-fourths of states, making change extremely rare (27 amendments in over 235 years). Britain needs only a simple parliamentary majority, allowing rapid restructuring of governance.

In short: the 27th Amendment would give Pakistan a —flexible, parliament-driven, and center-dominant—while moving it further from the durable federal balance and robust judicial independence. The result: a more agile but less constrained central government.