Instead of resolving small issues promptly, we keep postponing them, and these very small issues, lurking in hiding, eventually take the form of a major problem. These major issues then fall into the deep pit of a great crisis, where other problems join in and begin spreading rot. This rot spreads everywhere and engulfs everyone. For example, the minor habit of throwing garbage outside the house over time turns the entire area into a heap of filth.

When issues grow, they become entangled with one another like a dense forest. If this forest is of acacia trees, passing through it becomes impossible. Because not only do the thorns form a wall blocking the path, but the wild creatures (hidden in the dense forest) further increase the dangers. In such a situation, finding a way becomes extremely difficult.

If you grasp the thread of a major issue and trace it back to its roots, you will discover that behind it lies some powerful group or cartel controlling it. These very cartels, working together, create a dense forest of thorns and a pit of garbage in our midst and surroundings, in which we are all trapped.

Politics and resistance appear to have a deep connection, which is perhaps why politicians are often the target of criticism. In the past, politics used to be a field of thought and action. Thinkers like Aristotle, Socrates, Plato, Machiavelli, Morgenthau, Kant, and Chanakya touched the ultimate limits of thought. But leaders like Khrushchev, Hitler, Mussolini, Netanyahu, Modi, Hosni Mubarak, and Hasina Wajed demolished the walls of thought and awareness, plunging the world into darkness.

The habit of not resolving issues and the effects of their escalation are now becoming evident in the world. At this time, the world’s biggest challenge is to stop the deception of greedy merchants in the free market economy.

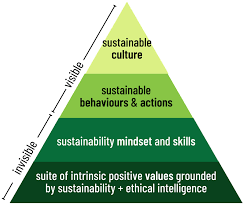

When small habits become ingrained, they become the character of individuals and societies. Forming queues, stopping at traffic signals, overtaking from the right side, speaking the truth, using trash bins, not spitting in public places, eating on time, washing hands before eating, going to bed early, and adhering to the five daily prayers—if these habits are part of our lives from childhood, then as adults we will pay taxes, give employees their salaries on time, and avoid adulteration or hoarding, because good habits prevent us from bad deeds. A good habit is a boundary that keeps us from wrong actions.

Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein’s book Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness (2008) is a useful guide for better shaping societies. Its core idea is “libertarian paternalism”—influencing people’s choices in predictable ways without restricting their freedom. The authors introduce “choice architecture”, the art of designing environments so that the path of least resistance leads to better outcomes. A famous example is placing healthy foods at eye level in cafeterias, subtly “nudging” people toward them while still allowing free choice.

Key concepts from Nudge include:

• Defaults: People stick with pre-set options (e.g., automatic enrolment in pension plans increases savings rates dramatically).

• Incentives: Small rewards or penalties can shift behaviour (e.g., fly-tipping fines or recycling rebates).

• Feedback: Immediate, clear information helps correction (e.g., home energy reports comparing your usage to neighbours reduce consumption).

• Expect error: Design systems assuming people will make mistakes (e.g., simplified tax forms).

• Structure complex choices: Break big decisions into smaller steps (e.g., “RECITE”: Reduce, Eliminate, Clarify, Incentivise, Test, Evaluate).

The book advises giving children complete freedom but nudging their small habits through smart choice architecture so that when they grow up, they make better decisions by default. These habits are nurtured through symbolic methods (symbolism), such as entering the mosque without shoes, which is a symbol of purity and respect—or school cafeterias placing fruit before desserts.

Symbols are like a movement. For example, stand in respect when the national anthem plays, fall silent when the adhan begins, do not enter someone’s house without permission, and recite Bismillah before starting to eat. In Western societies, societies have been organised through these small nudges disguised as restrictions. In particular, adherence to traffic laws and the habit of forming queues prove helpful in freeing one from selfishness—often achieved by simple defaults (e.g., painted lines on roads) or social feedback (e.g., disapproving looks). These nudges play a key role not only in individual character but also in the development of the entire society.