What world is witnessing right from begining of 2026 are not isolated incidents or happenings, but rather a web of interconnected flashpoints. There is a pattern in all happenings, US military’s operations in Venezuela, the potential settlement in Ukraine, the ongoing fights in Yemen, Syria, and Afghanistan, and the escalating tensions with Iran.These events are related by the same causes: fierce competition for resources and strategic chokepoints, the emergence of proxy warfare, the use of regime instability, and the broader struggle for power in a deteriorating unipolar order. To understand this pattern, one needs to see through the Great Power Competition ( GPC) paradigm. This realist paradigm demonstrates how the United States, Russia, China, India as well as Iran compete for security and dominance, frequently using smaller countries as battlegrounds. This analysis highlight that we are not witnessing an organized, bipolar “Cold War 2.0,” but rather a more dangerous and fragmented multipolar rivalry marked by an elevated risk of unintentional escalation and prolonged global instability. Let us see briefly what is happenging and where?

US attacks Venezuela:On January 3, 2026, US troops attacked and detained President Nicolás Maduro, claiming it was a “law enforcement” operation. Critics claim that the change in administration is illegitimate and is affecting Latin American politics as well as the global flow of oil. The battle between Russia and Ukraine is nearing its end. Talks have progressed, and a solution may be achieved as early as 2026.Despite Russian victories and Western security guarantees, engagement is ongoing, but many people remain dubious.

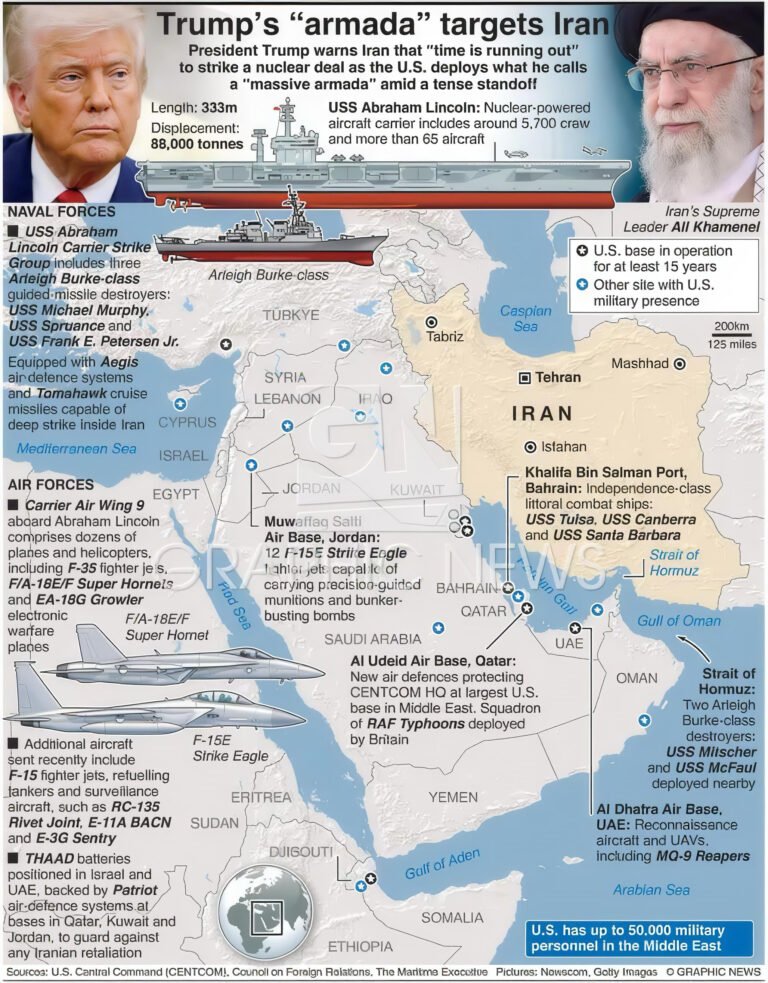

Iran’s riots and potential future violence: Since the United States and Israel struck Iranian nuclear sites in June 2025, nationwide protests against the regime have intensified. More strikes are being threatened against the weaker government.

Yemen Conflict: The Saudi-led coalition’s divisions have exacerbated the civil war. Territorial advances and pauses in aid exacerbate a bad humanitarian situation. We must not ignore the blocking of red sea, during Israel-Gaza war, by Hothis.

Syrian Fragmentation: After Assad’s government forces clash with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Aleppo, thousands of people are forced to flee their homes. If integration attempts fail, Turkey may join in, further fragmenting things.

Afghanistan has about 20 terrorist groups, including al-Qaeda and ISIS-K, which pose a direct threat to stability and neighboring countries.

Analysis using the Great Power Competition ( GPC) Framework

In GPC, governments prioritize survival and power in a rule-free society. This leads to alliances, proxy conflicts, and resource competition. These occurrences reveal significant patterns:

1. Resource Control: Energy, Minerals, and Digital Terrain Energy remains a critical factor: Venezuela’s oil, Ukraine’s pipelines, the Strait of Hormuz, and Yemen’s Bab al-Mandab Strait are all important. However, the battlefield has grown.China is increasingly and heavily involved in resource conflicts in Afghanistan, Africa, and elsewhere because it owns critical minerals (for technology and renewable energy) and digital infrastructure (5G, underwater cables). Simultaneously, an information war is underway in which tales are employed as weapons (for example, “law enforcement” vs. “regime change”) to justify actions and acquire power in the Global South. India heavily rely on fake news employing against Pakistan.

2. The Proxy Paradox: Transactional Allies and Backlash. Proxy battles allow you to deflect blame while simultaneously giving you less control. The intentions of the Houthis, Syrian Kurdish troops, and Afghan terrorist organizations frequently differ with those of their backers. This can result in policy failures or direct repercussions, such as when terrorists in Afghanistan threaten China’s interests in Pakistan. The weakening of these linkages, as seen by the deportation of a separatist leader in Yemen, exposes sponsors to sudden changes in policy.

3. Unstable Regime as the Universal Catalyst

State fragility is not a side effect of GPC; it is the primary fuel for it. Power vacuums in Caracas, Kyiv, Tehran, and Kabul make it simple for foreign forces to intervene. However, the “regime change” strategy is an extremely risky step. Short-term gains, such as those seen in Venezuela, are typically accompanied by long-term costs such as regional animosity, refugee crises, and a long-running insurgency. Taking advantage of internal upheaval in a country, such as Iran, can backfire, causing the regime to become more aggressive throughout the region.

4. The Escalation Engine: How Different Countries Are Connected in a World of Many Poles. The “ripple effects” occur immediately and are mechanical. The primary distinction between this and the Cold War is that there are no clear zones of influence or tacit rules.There are no functional modern counterparts of existing red lines or hotlines. A US attack on Venezuela alters Russia’s ambitions in Ukraine; an Israeli airstrike in Iran alters the Houthis’ actions in the Red Sea; and Turkey’s potential involvement into Syria pits a NATO member against a US-backed force. This increases the likelihood that small conflicts may grow and directly affect major countries.

Conclusion: A Choice Between Two Paths, The GPC framework emphasizes that we are fighting a long and hard battle for the new world order. The United States wishes to restore dominance, but a loose alliance of Russia, China, and Iran is fighting against it. In this system, middle powers are gaining power.This isn’t just another Cold War; it might be more unstable. The 20th-century deadlock included two disciplined factions and a powerful deterrence structure.Today’s multipolar struggle has many independent participants, the lines between war and peace are blurred, and non-state actors can have a global impact.So, the planet can adopt one of two paths:

1. Descent into a “Hot Peace”: An ongoing state of fragmented warfare in which proxy wars, terrorism, and resource nationalism become the norm, with each incident threatening rapid, uncontained escalation.

2. Transitioning to Managed Competition: This better solution entails accepting that in a world where everything is interconnected, zero-sum advantages are not real.It is critical to seize opportunities to reduce tensions in Ukraine, stabilize Venezuela through international cooperation, and address threats such as terrorism in Afghanistan in a constructive manner.The result is not predetermined. The pattern of Great Power Competition is evident, but the outcome—either a new era of managed restraint or a fall into systemic conflict—depends on whether states can build new, delicate guardrails for a globe that is already chilly in many places but too interconnected to risk a full freeze.

Great tremendous issues here. I am very satisfied to peer your post. Thanks so much and i am having a look forward to touch you. Will you please drop me a mail?