In the fragmented multipolarity of 2026, the world grapples with an escalating polycrisis, characterized by geopolitical volatility, intensified great-power competition, and the urgent demands of the green energy transition. This landscape, shaped by the disruptive policies of a second Trump administration, reveals a state of fragmented interdependence where traditional tools of statecraft fall short against 21st-century transnational challenges. Viewing this through the main lenses of International Relations (IR) theory—Realism, Liberalism, Constructivism, and Critical Theories—highlights the interplay of power, institutions, narratives, and inequalities. Pakistan, as a mid-tier power with strategic geography, nuclear capabilities, a population exceeding 240 million, and untapped mineral resources valued at over $1 trillion, exemplifies this dynamic. It navigates the US-China rivalry with “Middle Kingdom” diplomacy, hedging between superpowers while asserting regional influence in South Asia, the Middle East, and Central Asia. This positioning not only blurs bloc alignments but also amplifies Pakistan’s role amid climate-induced instability, militant threats, and economic imperatives.

Realism: Power Competition in a Messy Multipolar World

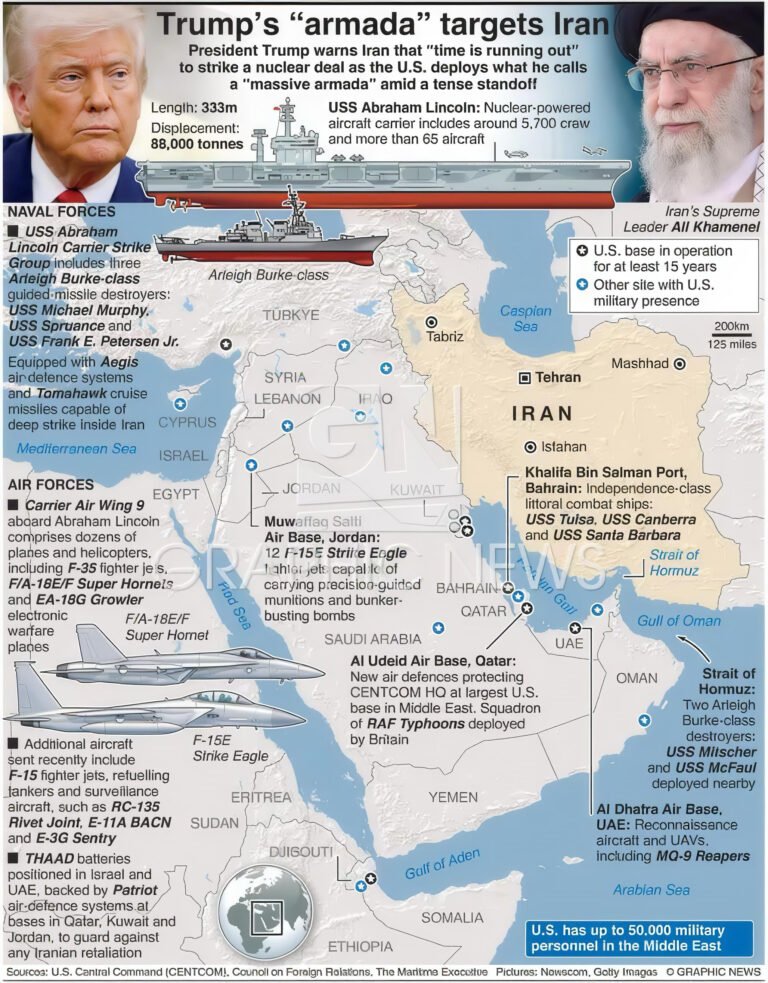

Realism provides the most compelling framework for understanding 2026’s core dynamics, where states prioritize survival, relative power, and security in an anarchic system. The US-China rivalry has evolved into a tense but managed bipolarity in domains like technology and the Indo-Pacific, while fostering a messy multipolarity globally. Regional powers such as India, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, and Pakistan exploit this fluidity through hedging, transactional alliances, and balancing strategies. Military modernization surges, with investments in anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities, drones, autonomous systems, and cyber tools. Conflicts persist in gray zones or through proxies, including the lingering aftermath of Ukraine, instability in the Sahel, frictions in the South China Sea, and pressures in the Taiwan Strait, averting direct great-power clashes.

Competition over critical minerals for technology and the green transition fuels alliances and rivalries. China dominates processing and rare earths, using export controls as leverage, while the US bolsters domestic resilience through initiatives like the Minerals Security Partnership. Realists see climate change as a source of instability—triggering resource wars, migration crises, and water disputes—to be exploited for national gain. Flashpoints like the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait remain high-risk, where minor shifts could escalate rapidly.

Pakistan embodies this realist paradigm through its security dilemmas and power balancing. Its nuclear arsenal and military upgrades, supported by Chinese technology transfers and joint exercises, deter rival India amid simmering post-2025 skirmishes. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), now exceeding $60 billion in investments, secures energy routes and counters Indian influence in Afghanistan. However, 2026 witnesses a pragmatic pivot toward the US under Trump’s opportunistic diplomacy, including high-level meetings with Field Marshal Asim Munir and Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif. This “strategic ambiguity” exploits the US-China standoff: Beijing offers infrastructure and debt relief, while Washington provides sanctions relief and military support against Afghan-Pak border clashes with the Taliban. Pakistan leverages its asserive and stabilizing role, respectively in South Asia and Middle East . Yet, domestic challenges, particularly polarization, terrorism remains a problem. Flashpoints like the Afghanistan border and Kashmir, marked by early 2026 cross-border strikes against the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), maintain fragile ceasefires but risk escalation involving India or Iran.

Liberalism: Strained Interdependence and Eroding Institutions

Liberalism underscores the persistence, albeit corrupted, of economic interdependence and institutional cooperation, even as core bodies like the UN, WTO, and IMF lose legitimacy. Mini-lateral and regional forums, such as expanded BRICS+ and ASEAN-led mechanisms, emerge as alternatives. Supply chains reorganize through friend-shoring and blocification into geopolitically aligned groups (e.g., US-EU-Japan versus China-Russia-centric), politicizing trade and prioritizing security over efficiency. Non-state actors, particularly tech giants in AI and space, exert state-like influence, posing governance challenges.

Pockets of cooperation endure, especially in climate finance and loss-and-damage mechanisms, spurred by severe 2024–2025 climate events and humanitarian needs. Nonetheless, liberalism appears strained: institutions persist but underperform, with “secure” interdependence eclipsing global optimism.

For Pakistan, liberalism manifests in pursuing “secure” interdependence via mini-lateral forums and blocification. Expanded BRICS+ membership and ASEAN ties offer alternatives to the IMF, where Pakistan’s $130 billion external debt (over 80% of GDP) drives reforms. Friend-shoring with the US-EU bloc, through mineral exports and tech initiatives like Google’s 500,000 Chromebook production by 2026, diversifies from China-centric chains. Multinational corporations in AI and rare earths enhance this, with US firms targeting Pakistan’s resources .

Constructivism: Clash of Narratives and Identities

Constructivism reveals how ideas, norms, and identities shape the international system. In 2026, a contest unfolds between the Western “autocracy vs. democracy” narrative and the China-Russia “sovereignty vs. hegemony” frame. Alignments increasingly align with civilizational or political identities, while norms like the “rules-based order” and “responsibility to protect” face contestation. Digital sovereignty and cyber accountability norms fragment further. Domestic identity politics—such as US election fallout, EU cohesion issues, and leadership transitions—reshape foreign policies. The concept of “security” expands to include economic resilience, technological supremacy, and environmental stability, influencing alliances.

Pakistan’s constructivist approach centers on its “sovereignty vs. hegemony” narrative against Indian dominance and Western interference, fostering strategic autonomy. Civilizational ties drive pacts with Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Azerbaijan under Muslim unity, while anti-hegemonic discourse aligns with China-Russia against Western frames. Pakistan contests US tech dominance via Chinese 5G infrastructure, testing cyber norms in border conflicts. The broadened security definition—encompassing CPEC Phase II for economic resilience and post-flood environmental stability—positions Pakistan as a “bridge” between East and West.

Critical Theories: Enduring Hierarchies and Extraction

Critical theories (Marxist, post-colonial, feminist) uncover persistent inequalities. The green transition risks perpetuating core-periphery dynamics, with the Global South supplying minerals on unequal terms, often termed “green colonialism,” amid IMF debt leverage. North-South divides intensify over climate justice, digital access, and resource equity. Expanded BRICS+ seeks counter-hegemony but with limited success. Conflicts, displacement, and austerity disproportionately burden women and minorities, sparking protests as resistance to the global capitalist order.

Pakistan’s critical vulnerabilities highlight neo-imperial dynamics: as a Global South mineral supplier, it faces “green colonialism” from US opportunism and Chinese investments. IMF leverage amid climate shocks widens divides, fueling protests over food insecurity and austerity. Terrorist outfits in Afghanistan and their foreign financiers remain a problem for Pakistan.

Overall: Fragmented Interdependence in Polycrisis

No single IR paradigm dominates 2026; instead, they intersect to depict a world of security competition (Realism), strained institutions (Liberalism), narrative clashes (Constructivism), and systemic inequalities (Critical Theories). The polycrisis—interweaving climate shocks, economic instability, migration, and technological disruptions like AI and biotech—overwhelms capacities, prompting reactive policies. Mid-tier powers, including Pakistan, India, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Indonesia, and Brazil, exploit the US-China standoff for maneuvering space, blurring blocs through hedging.

Pakistan’s role epitomizes this: its “geopolitical renaissance”—via defense pacts, mineral deals, and Afghan operations—grants leverage, but domestic unrest and polycrisis risks overstretch. In essence, 2026 applies outdated statecraft to modern problems, finding it inadequate. The true contest lies in responses to crises—through balancing, cooperation, narratives, or change—determining winners in this unsettled, multipolar transition. Pakistan, as a pivotal hedger and regional stabilizer, shapes outcomes but teeters between triumph and vulnerability, hinging on adaptive strategies balancing autonomy and alliances.